Everybody get together now.

The rise and fall of the traveling music festival.

If you were old enough to be going to shows in the ‘90s, you couldn’t deny the presence or pull of multi-band outings that toured the country at the time. Lollapalooza. H.O.R.D.E. The Warped Tour. The Lilith Fair. OzzFest. Hell, even country figurehead George Strait had his own packaged assemblage of up-and-coming and established artists that opened for him (and yes, I saw that too). Each was framed under a thematic banner with a name that reflected their musical genres and served as a way to rally their relative subcultures.

This type of rambling roadshow wasn’t an entirely new construct. Since the earliest days of blues, R&B, soul and rock n’ roll, individual artists and bands have aligned to provide audiences with an occasionally rotating variety bill of sorts that barnstormed city to city. In the ‘70s and ‘80s you had massive one-off shows and festivals that became pop-culture milestones, from Fleetwood Mac, The Who and The Rolling Stones to Monsters of Rock, which was a peak at the time for the popularity of hard rock and featured legacy headbangers like Van Halen and The Scorpions but also marked the ascendancy of aspirants to the throne like Metallica (I’m still somewhat displeased with my mom for not letting me drive with friends from San Diego to a vast field an hour east of LA to see the US Fest in 1983 when I was 16. Here’s a VH1 documentary.).

The Police onstage at the US fest in Glen Helen, CA in 1983.

In the ‘90s, festivals took on a different shape and meaning and as a result, created impact we still feel today. Part of that was due to the landscape at the time, relative to how we actually consumed music. There was no streaming, social media or immediate access to an unending array of artists of whom you’d never heard. Radio was still a controlling and influential presence, particularly what were known as AOR (album-oriented rock) stations.

There were a handful of “alternative” stations in larger markets around the country that could flex some muscle on small budgets, but non-mainstream artists were still largely relegated to college-radio stations you had to seek out (that were always, as the beloved Replacements solidified in song, “left of the dial.”). MTV remained a force in the early ‘90s but towards the end of the decade would teeter into the reality-TV void that ironically saw them leave the music largely behind forever.

By creating some collective-bargaining power and newfound appeal with promoters, a well-organized festival in theory could not only gain some notoriety and break new artists, but also sell some tickets (and merch and CDs) and give audiences a great day of varied entertainment. There were economies of scale to be gained, while also relative autonomy that in most cases outweighed the inherent risk.

But in trying to maintain interest with fans from year to year, they were still up against radio stations that could twist arms with labels and management. By promising what any artist understandably wanted, radio air time, labels could fill their own festival lineups with whatever bands were happening at the moment. Which they did to directly protect their turf, particularly in the summertime.

It was a fleeting, fluid and fertile period in time for both music and culture. Artists felt emboldened and the general attitude seemed, “why not?!” The wind was at their back, the timing felt right, or so they thought. So let’s dive into some detail about the aforementioned festivals that really helped shape the decade:

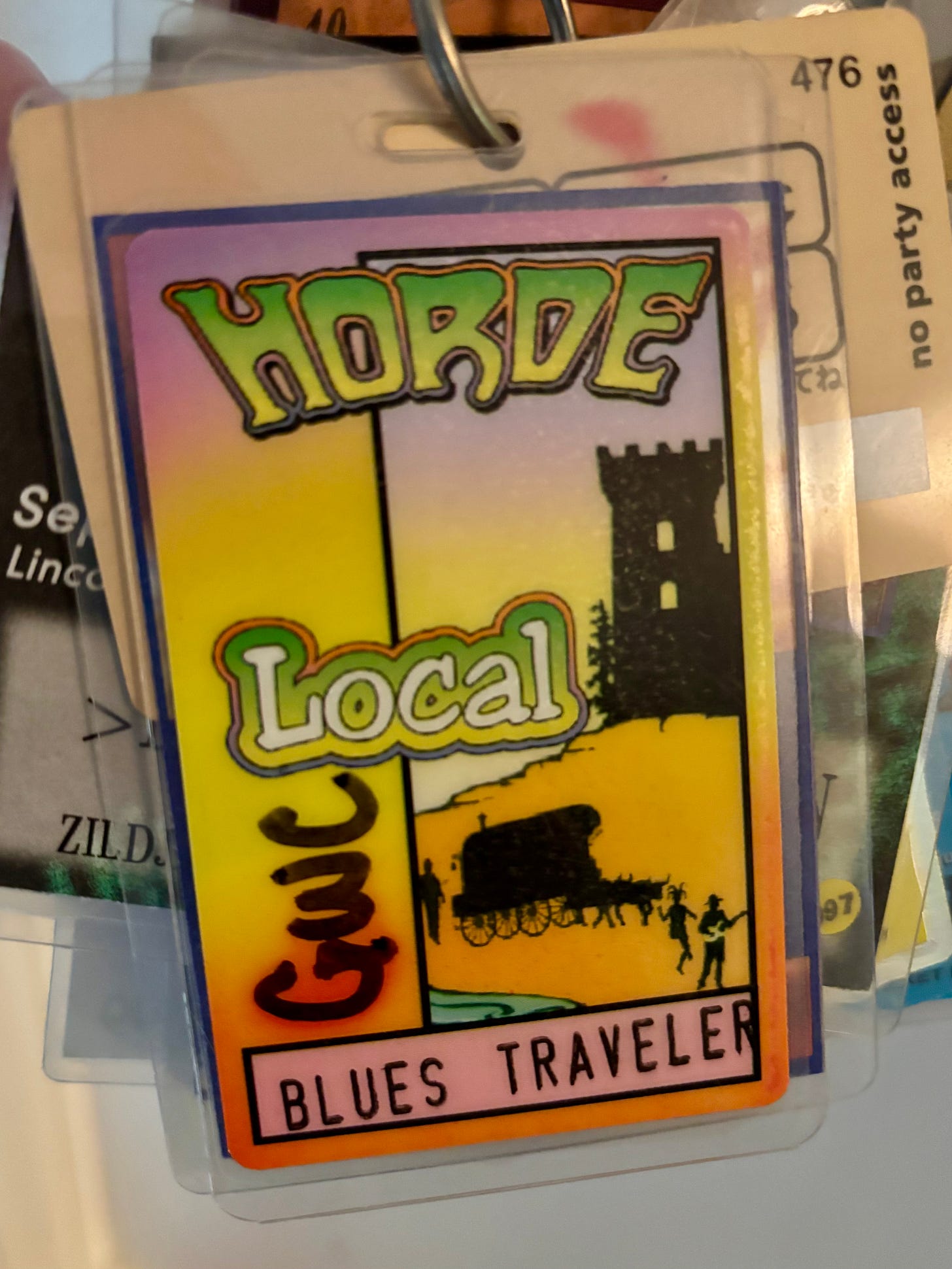

H.O.R.D.E.

H.O.R.D.E. was the brainchild of jam-blues band Blues Traveler, who in 1992 gathered together fellow east-coast bands like the Spin Doctors, Widespread Panic and Phish as a means to avoid playing the club circuit in the summertime when other larger bands were selling out amphitheaters. The name was an acronym for “Horizons of Rock Developing Everywhere,” and Blues Traveler correctly assumed that literally banding together would make for a worthwhile endeavor. The tour grew to include artists like the Black Crowes, Ziggy Marley, Neil Young, Barenaked Ladies, Lenny Kravitz and the Dave Matthews Band.

The two H.O.R.D.E. fests I attended had a distinctly peace and love, patchouli-scented aura that served as a magnetic tractor beam for both new and latent Grateful Dead fans, despite the fact that there were many bands on the bill who would probably chafe at being connected to that scene (I knew I did). But due respect, H.O.R.D.E. ran for six years and staged its last show in 1998 after playing 40 dates across the country.

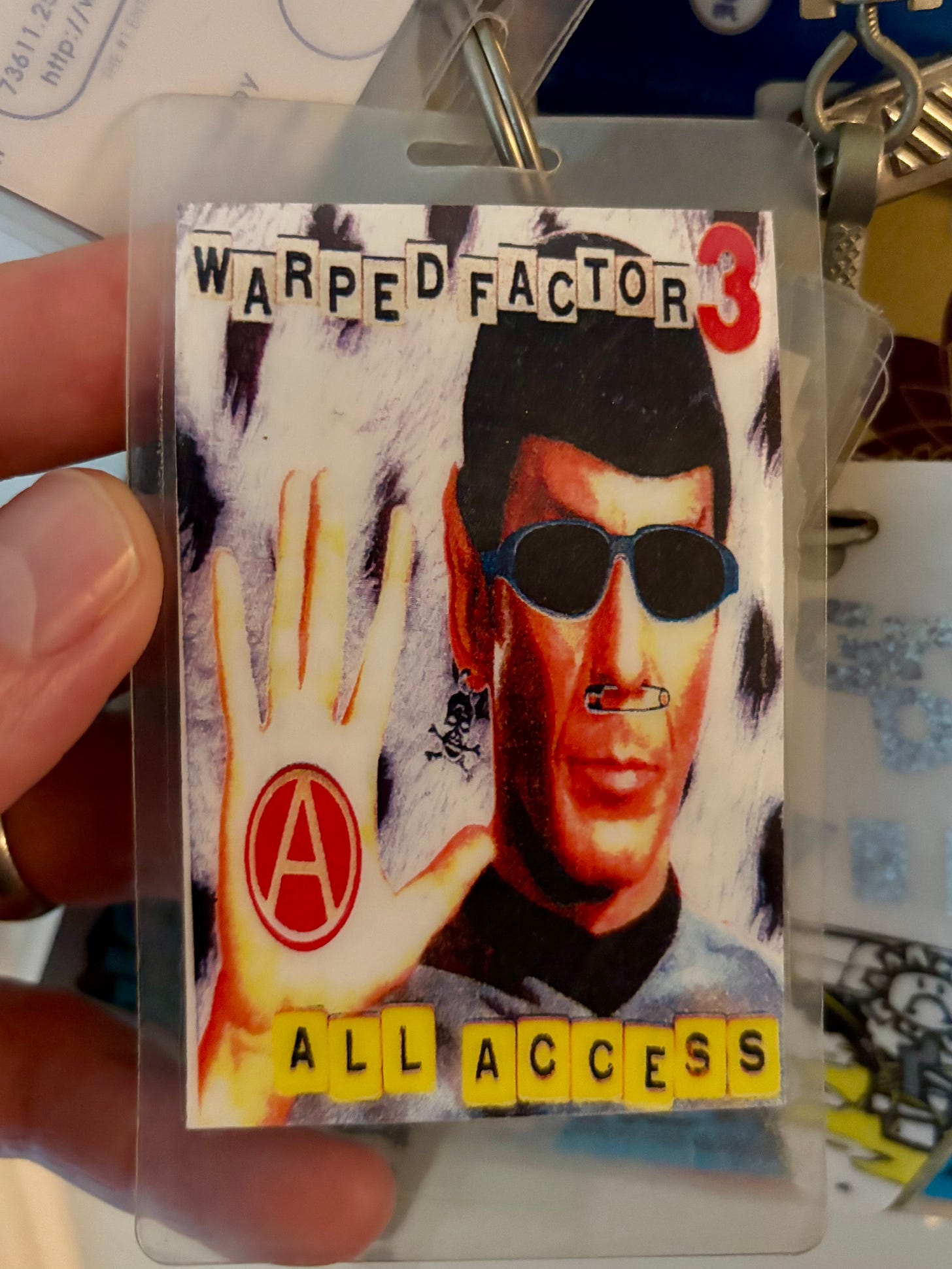

The (Vans) Warped Tour

Unofficially known as “punk rock summer camp,” The Warped Tour was started in 1995 by an LA promoter I knew, Kevin Lyman. It originally featured skate-punk and third-wave ska bands but ventured in later years into metal, hardcore and other genres. In fact, in the aughts it helped break now hugely mainstream artists like Paramore, Fall Out Boy and Katy Perry.

Since each stop was different, the tour would change shape from venue to venue. It often revolved around a setup with stages at either end of a common area that had vendors and skate and other action sports demos. Warped was a truly celebratory carnival for every kid that dressed largely in black in high school, frequented the smoking section and hung out at the local skate park.

I was at the original tour in 1995 and the following two years, before moving to Boston and later to my current home of Kansas City. In all those places I always went because the skate kid in me always came out of hiding when the latest lineup was announced and it was always a blast of a scene where I could both watch with friends in the crowd and hang out with band friends backstage.

In 1996, Vans came calling to sponsor the tour. It was an early example of what we now know all too well as corporate interests hitching themselves to pop-culture in order to profit. With Vans, it actually made sense. The company had been making shoes since 1966 in Anaheim and was fully vested in the skate scene. And punk and skating were inextricably linked. We all wore and loved Vans, so the connection seemed less leech-like and more of an appropriate partnership. It remained until the fest ended in 2019.

I can’t remember whose bus I was on at the time or what Lollapalooza this was, but man just check out that upholstery!

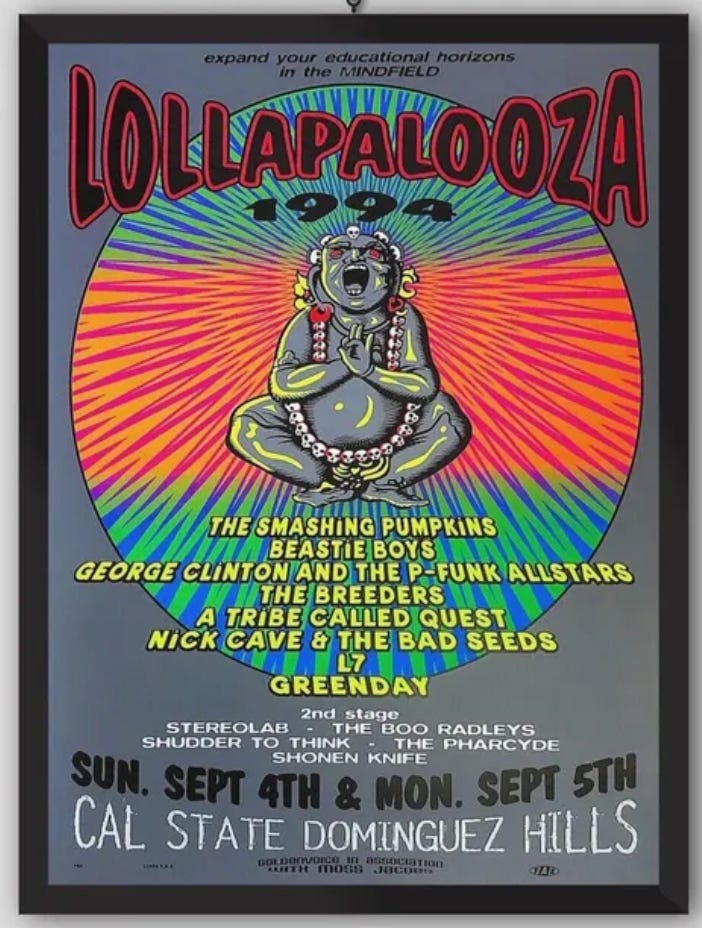

One of my more favorite Lollapalooza lineups and days out south of LA.

Lollapalooza

The story of Lollapalooza is well known by now and its familiarity embedded in American culture by everyone who still attaches an “alooza” suffix to a word to infer some sort of larger event. What was started by Jane’s Addiction frontman Perry Farrell in 1991 as a farewell tour for a band sadly nearing self-destruction and an homage to England’s Reading festival became something much much bigger.

In the early ‘90s, alternative acts weren’t filling large venues. It was audacious at the very least to suggest to promoters that an assemblage of said artists would make everyone some money. But driven by word of mouth, favorable MTV coverage and a relatively diverse array of artists that included Nine Inch Nails, that first tour sold out a majority of its stops. The next year it added a side stage and the Lollapalooza model became fully shaped.

Those first years, as is perhaps true with so many well intentioned ideas that become bigger than expected, were the purest in terms of alt-rock music and staying true to intent. But as interest grew from artists and audiences alike, the festival started to feel at odds with itself. After all, it’s hard to be the beating heart of the underground when that culture has risen above the surface. By 1994, Lollapalooza was so successful that Nirvana turned down a $6 million headliner offer, lest the band be seen as the worst thing it could imagine: a sellout. Kurt Cobain tragically died not long after.

I attended multiple Lollapalooza shows after moving back to the U.S. in early 1993, but honestly never saw another one after I left the job in 2000. The fest went through fits, starts and hiatuses for years until it was repurposed by a new promoter in 2005 into the Lollapalooza we know today, a three-day affair held only in Chicago where far more mainstream and legacy acts perform alongside younger upstarts.

Regardless, Lollapalooza proved that large-scale, genre-bending weekend fests were a model that could work, as born out more recently by celebrated events like Coachella and Bonnaroo. Its lasting success also showed that the music industry and the media that covers it often underestimate the power and potential of certain scenes and subcultures until they’re packaged in the right way. (Paramount + has a documentary about it all.)

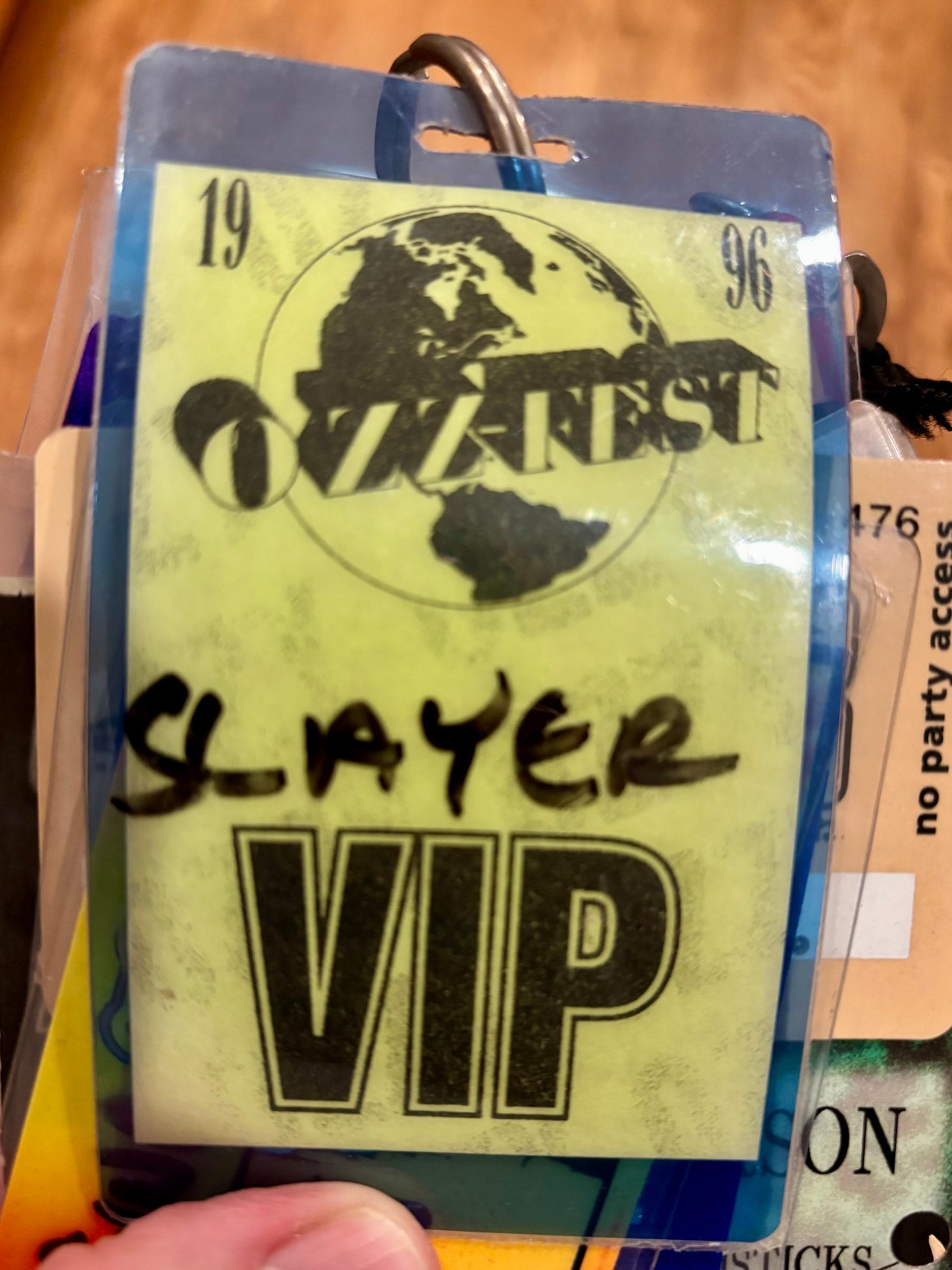

OzzFest

We sadly lost Ozzy Osbourne this past year, but the man’s incredible legacy will never be extinguished. His manager-wife Sharon remains a notorious figure who guided much of his life and career. In 1996, after Lollapalooza thumbed its nose at the idea of adding Ozzy to the tour, she decided to create a new festival dedicated to metal and hard rock called OzzFest.

It was an immediate hit with hordes of finger-horn throwing metalheads who long felt ignored, particularly as “alternative rock” gained greater traction on radio through the ‘90s. The bands who played OzzFest stages ranged from established powerhouses like Slayer, Pantera, Tool, Rage Against The Machine and Megadeth to insurgent nu-metal upstarts like Limp Bizkit, Korn, Marilyn Manson and System of a Down. Later in the aughts it would go global and bring in giants like Iron Maiden and Judas Priest.

The best part beyond the music to me was the crowd itself. You know those scenes in “The Lord of the Rings” where throngs of Orcs assemble as armies to seek and destroy? That’s what every OzzFest felt like to me, a glorious sea of self-admitted societal misfits out for the time of their lives. Faces pierced, hair dyed, denim shredded and studded, arms and legs inked to the hilt (sometimes in hilariously regrettable fashion, could make a book of those tattoos), beer flowing, people passed out and porta potties definitely to be avoided at all costs if possible.

The Lilith Fair

There’s a quite enjoyable documentary running on Hulu right now about the pioneering Lilith Fair festival, which was the first to not only be started and run by women (in particular singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan), but that also featured a lineup comprised entirely of female artists or women-led bands.

The name referenced a Biblical figure Lilith, embraced as a symbol of feminism and independence. To hear McLachlan tell it, “Lilith Fair was created for many reasons: the joy of sharing live music; the connection of like minds; the desire to create a sense of community that I felt was lacking in our industry.”

It was also a forceful rebuke to what these artists saw as transparent disrespect and disregard of female voices in music. Promoters insisted that people wouldn’t come to see multiple women on the same bill. In hindsight it seems ridiculously outdated, but it was very much true at the time.

The tour immediately proved them wrong, launching at the Gorge Amphitheater in Washington state with a sold-out show on July 5, 1997. It went on to 37 stops and featured 69 acts that included McLachlan, Fiona Apple, Tracy Chapman, Sheryl Crow and the Indigo Girls. It also became the highest grossing tour of that year.

Despite breaking many new artists, highlighting other luminaries like Bonnie Raitt, Lauryn Hill and Sinead O’Connor and otherwise being hugely lucrative, the tour came to an end after just three years in 1999. I took my now wife to that last summer show in Boston, where she got her first real taste of backstage starfucker overload.

While sharing a beer with her in between sets at the Great Woods amphitheater, I noticed Sheryl Crow and CHRISSIE FUCKING HYNDE with acoustic guitars working out a song across the patio from us. I encouraged her to go say hi, that they’re just people (albeit occasionally prickly ones), despite her starstruck hesitation. She briefly did, and then shared with me her emotional takeaway: Watching Chrissie quickly trying to learn the words to Sheryl’s song so they could perform it, perhaps feeling uncomfortable for a minute but being confident enough as the woman she was to just go out and do it. Which in ways was the larger meaning to the festival as a whole.

Our current reality being what it is, I firmly believe we’ll never again experience such a flurry of truly communal events like we did in the ‘90s. Too many forces now exist that make them financially and logistically prohibitive at best. Supportive labels are barely a thing anymore and artists are largely masters of their own destiny. Ticketing, radio, venues, they’re all now monopolized by larger corporations like Ticketmaster, Live Nation, AEG and others which demand an ever-larger piece of the proverbial pie.

Meanwhile, subcultures largely only exist online or at expensive one-off get-togethers in convention halls. Live music scenes like those that thrived 30 years ago because we needed to be “among our people” in real life are that much more difficult to sustain. Every show I go to now, half the crowd has their phones up the whole time.

This isn’t a yelling at clouds moment, but rather just a bit of a lament, for myself as well as my young adult kids. Our race to commodify literally everything has sapped so much life from more meaningful experiences. Our willingness to rely on technology more than our humanity often hinders us from being fully present in the moment or focused on anything but ourselves. Our glorification of greed misplaces priorities, drives us further apart and makes things that were once attainable for more people far less so. And even festivals aren’t immune to any of that anymore.

As always when going down these mental rabbit holes I do so dearly wish I had more photographic evidence of all that occurred. I plead too many moves and too few times having an actual camera on my person when doing my job. Not that the memories are any less vivid.

What a great recounting of what was and why it was so important (& all we miss about these times). My favorite line is about Wendy’s first “backstage starfucker overload.”😆 KEEP WRITING.

Super!